Содержание

Bazaar - это инструмент помогающий людям сотрудничать. Он отслеживает изменения, которые вы и другие люди делают с группой файлов, (таких как исходный код программы) для того что бы дать вам снимок каждого этапа их эволюции. Используя эту информацию, Bazaar может без проблем объединить вашу работу с работой других людей.

Такие инструменты как Bazaar называются системами контроля версий (Version Control System (VCS)) и уже долгое время популярны среди разработчиков ПО. Легкость использования, гибкость и простота настройки Bazaar делают его идеальным не только для разработчиков ПО, но так же и для других групп, работающих совместно с файлами и документами, таких как технические писатели, Web-дизайнеры и переводчики.

Это руководство описывает установку и использование Bazaar вне зависимости от того работает вы один, или в команде с другими людьми. Если вы уже знаете, что такое распределенная система контроля версий и хотите перейти прямо к описанию работы вы можете бегло просмотреть эту секцию и перейти прямо к Продолжаем изучение.

Инструменты для контроля версий на данный момент развиваются уже в течение нескольких десятилетий. Простыми словами можно описать 4 поколения таких инструментов:

- инструменты контроля версий файлов, например CSSC, RCS

- инструменты контроля дерева файлов - централизованный стиль, например CVS

- инструменты контроля дерева файлов - централизованный стиль, этап 2, например Subversion

- инструменты контроля дерева файлов - распределенный стиль, например Bazaar.

Дизайн и реализация Bazaar учитывает уроки полученные на каждом из этих этапов развития подобных инструментов. В частности, Bazaar аккуратно поддерживает и централизованную и распределенную модели контроля версий и таким образом вы можете менять модель работы (когда это имеет смысл) без необходимости смены инструмента.

Многие традиционные инструменты контроля версий требуют наличия центрального сервера, который хранит историю изменений (или репозиторий) для дерева файлов. Что бы работать с файлами пользователю необходимо установить соединение с сервером и получить рабочую версию файлов. Таким образом пользователь получает рабочее дерево в котором он может работать. Для сохранения, или фиксации изменений пользователю нужен доступ к центральному серверу и он должен убедиться, что перед фиксацией он объединил свою работу с последней версией сохраненной на сервере. Такой подход известен как централизованная модель.

Централизованная модель проверена достаточно долгой практикой, но она имеет и некоторые значительные недостатки. Во-первых, централизованная система требует наличия соединения с сервером при выполнении большинства операций по контролю версий. Во-вторых, централизованная модель жестко связывает момент фиксации изменений с моментом их публикации. В каких-то ситуациях это может быть нормально, но может сказываться негативно в других.

Распределенные системы контроля версий позволяют отдельным пользователям и командам иметь несколько репозиториев, вместо одного центрального. В случае с Bazaar история обычно хранится в том же месте, что и код который находится под контролем версий. Это позволяет пользователю фиксировать свои изменения в любой момент когда это нужно, даже при отсутствии сетевого соединения. Сетевое соединение требуется только для публикации изменений, или когда нужен доступ к изменениям в другом месте.

На самом деле для разработчиков использование распределенных систем контроля версий может иметь другие преимущества, кроме очевидных, связанных с работой при отсутствии сетевого соединения. Другие преимущества включают:

- более легкое создание разработчиками экспериментальных веток

- более легкое сотрудничество с другими разработчикам

- меньше времени требуется для механических задач и больше для творчества

- увеличение гибкости в управлении релизами через использование фиксаций включающих набор изменений для конкретной функциональности

- качество и стабильность основной ветки может быть выше, что делает работу проще для каждого

- для сообществ с открытым исходным кодом:

- более легкое создание и поддержка изменений для сторонних разработчиков

- упрощение взаимодействия основных разработчиков со сторонними разработчиками и более простая миграция сторонних разработчиков в основные

- для компаний - упрощение работы с распределенными и внешними командами.

Для более детального взгляда на преимущества распределенных систем контроля версий по сравнению с централизованными смотрите http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/BzrWhy.

Хотя Bazaar не единственная распределенная система контроля версий, она имеет некоторые значимые преимущества, которые делают ее прекрасным выбором для многих команд и сообществ. Описание этих особенностей и сравнение с другими системами контроля версий может быть найдено на Wiki Bazaar - http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com.

Из большинства особенностей, одна требует особого упоминания: Bazaar - это полностью свободное ПО написанное на языке Python. Это упрощает сотрудничество для внесения улучшений. Если вы хотите помочь, обратите внимание на http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/BzrSupport.

Это руководство представляет из себя легкое для чтения введение в Bazaar и описание его использования. Всем пользователям рекомендуется прочесть хотя бы окончание этой главы, так как:

- она описывает основные концепции, которые нужно знать пользователям

- она описывает некоторые популярные пути использования Bazaar для сотрудничества.

Главы 2-6 более детально описывают использование Bazaar для выполнения различных задач. Большинству пользователей рекомендуется прочесть их одну за другой сразу после начала использования Bazaar. Глава 7 и дальше содержат дополнительную информацию, которая поможет получить максимум от Bazaar после того как понятны основные функции. Этот материал может быть прочитан когда потребуется и в любом порядке.

Если вы уже хорошо знакомы с другими системами контроля версий, вы возможно захотите вникнуть скорее через чтение следующих документов:

- Bazaar за пять минут - небольшое введение

- Bazaar. Карточка быстрого старта - наиболее часто используемые команды на одной странице.

Плюс к этому справка на сайте и Справка по Bazaar предоставляют все детали по доступным командам и опциям.

Мы надеемся, что вам понравится это руководство. Если у вас есть пожелания по улучшению документации Bazaar вы можете написать в список рассылки bazaar@lists.canonical.com.

Для использования Bazaar нужно понимать четыре основные концепции:

Давайте рассмотрим каждую концепцию более детально.

Ревизия - это снимок состояния дерева файлов и каталогов включающий их содержимое и форму. С ревизией так же связаны некоторые мета-данные, например:

Ревизии не изменяются и могут быть глобально и уникально идентифицированы идентификатором ревизии. Пример идентификатора:

pqm@pqm.ubuntu.com-20071129184101-u9506rihe4zbzyyz

Идентификаторы ревизий создаются во время фиксации, или, в случае импорта из других систем, в момент импорта. Хотя идентификаторы ревизий необходимы для внутреннего использования и интеграции с внешними инструментами, специфичные для веток номера ревизий предпочтительны для людей.

Номера ревизий - это разделенные точками десятичные идентификаторы, такие как 1, 42 и 2977.1.59, которые отслеживают путь через граф номеров ревизий на ветке. Номера ревизий обычно короче чем идентификаторы ревизий и, в пределах одной ветки, могут сравниваться друг с другом для получения картины их отношений. Например, ревизия 10 - это основная ревизия (см. ниже) следующая непосредственно после ревизии 9. Номера ревизий создаются налету, при выполнении каждой команды, т.к. они зависят от ревизии являющейся верхушкой (т.е. самой последней ревизией) на ветке.

Смотрите Определение ревизий в приложениях для более детального описания огромного количества методов задания ревизий и их диапазонов в Bazaar и Понимание номеров ревизий для более детального описания нумерации ревизий.

Рабочее дерево - это каталог под контролем версий содержащий файлы которые может редактировать пользователь. Рабочее дерево связано с веткой.

Многие команды используют рабочее дерево как контекст, например commit создает новую ревизию используя текущее содержимое файлов в рабочем дереве.

В простейшем случае, ветка - это упорядоченная серия ревизий. Самая последняя ревизия известна как верхушка.

Ветки могут быть разделены и объединены обратно, формируя граф ревизий. Технически, граф показывает прямые отношения (между родительской и дочерними ревизиями) и не имеет петель, и известен как направленный ациклический граф (directed acyclic graph (DAG)).

Но не стоит бояться этого названия. Основные вещи которые нужно помнить:

Репозиторий - это просто хранилище ревизий. В простейшем случае, каждая ветка имеет свой собственный репозиторий. В других случаях имеет смысл разделять репозиторий между ветками для оптимизации дискового пространства.

Как только вы поняли описанные выше концепции, различные пути использования Bazaar станут более понятными. Простейший способ использования Bazaar - это использовать самостоятельное дерево, совмещающее рабочее дерево, ветку и репозиторий в одном месте. Другие часто используемые сценарии включают:

Лучший путь для использования Bazaar конечно зависит от ваших потребностей. Давайте дальше рассмотрим некоторые часто употребляемые способы использования.

Bazaar supports many different ways of working together. This means that you can start with one workflow and adapt it over time as circumstances change. There is no “one true way” that always makes sense and there never will be. This section provides a brief overview of some popular workflows supported by Bazaar.

Keep in mind that these workflow are just some examples of how Bazaar can be used. You may want to use a workflow not listed here, perhaps building on the ideas below.

Whether developing software, editing documents or changing configuration files, having an easy-to-use VCS tool can help. A single user can use this workflow effectively for managing projects where they are the only contributor.

Advantages of this workflow over not using version control at all include:

- backup of old versions

- rollback to an earlier state

- tracking of history.

The key features of Bazaar appropriate for this workflow are low administration (no server setup) and ease of use.

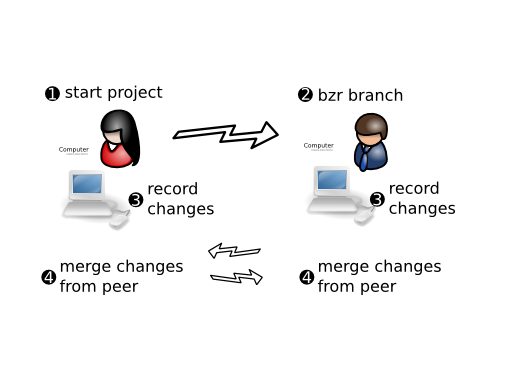

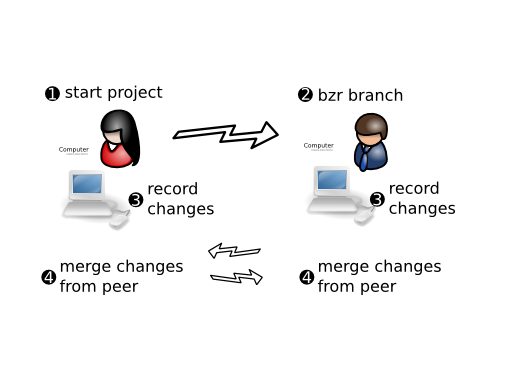

Sometimes two people need to work together sharing changes as they go. This commonly starts off as a Solo workflow (see above) or a team-oriented workflow (see below). At some point, the second person takes a branch (copy including history) of what the first person has done. They can then work in parallel exchanging changes by merging when appropriate.

Advantages over Solo are:

- easier sharing of changes

- each line of each text file can be attributed to a particular change including who changed it, when and why.

When implementing this workflow, Bazaar’s advantages over CVS and Subversion include:

- no server to setup

- intelligent merging means merging multiple times isn’t painful.

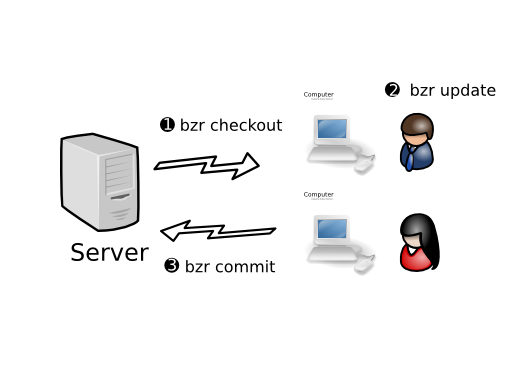

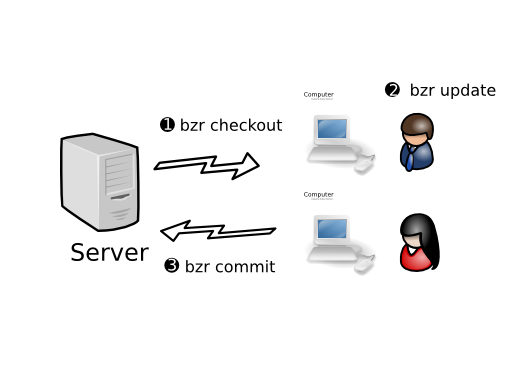

Also known as lock-step, this is essentially the same as the workflow encouraged/enforced by CVS and Subversion. All developers work on the same branch (or branches). They run bzr update to get their checkout up-to-date, then bzr commit to publish their changes to the central location.

Subversion and CVS are good choices for implementing this workflow because they make it easy. Bazaar directly supports it as well while providing some important advantages over CVS and Subversion:

- better branching and merging

- better renaming support.

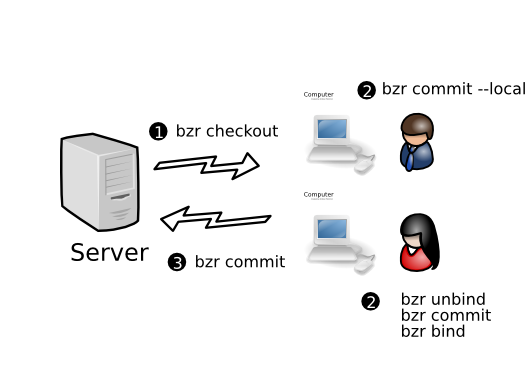

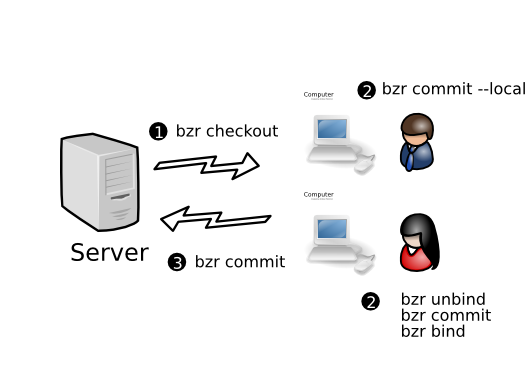

This is essentially the same as the Centralized model, except that when developers are making a series of changes, they do commit --local or unbind their checkout. When it is complete, they commit their work to the shared mainline.

Advantages over Centralized:

- Can work offline, e.g. when disconnected during travel

- Less chance for a bad commit to interfere with everyone else’s work

Subversion and CVS do not support this model. Other distributed VCS tools can support it but do so less directly than Bazaar does.

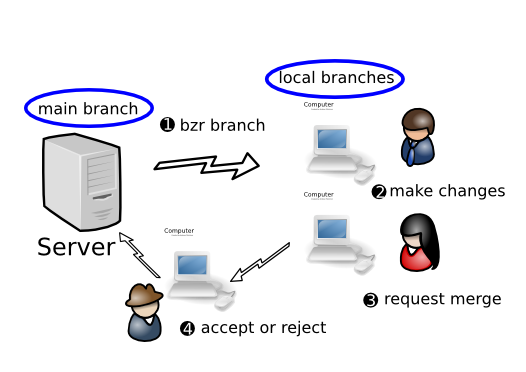

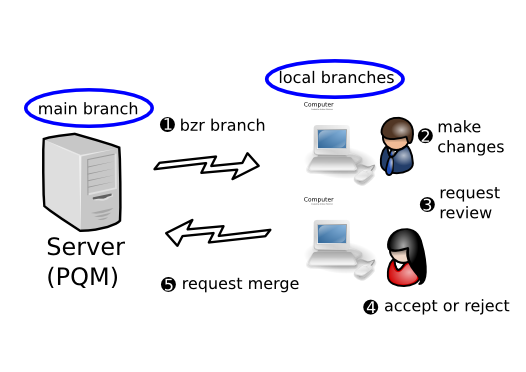

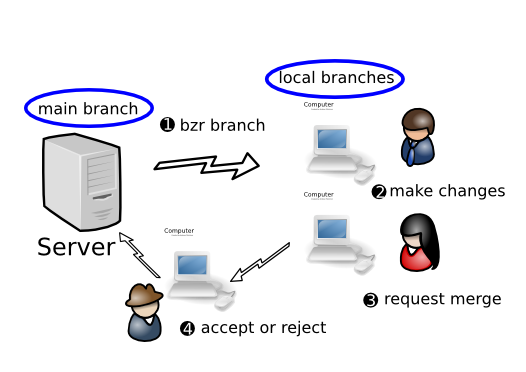

In this workflow, each developer has their own branch or branches, plus read-only access to the main branch. One developer (the gatekeeper) has commit rights to the main branch. When a developer wants their work merged, they ask the gatekeeper to merge it. The gatekeeper does code review, and merges the work into the main branch if it meets the necessary standards.

Advantage over Decentralized with shared mainline:

- Code is always reviewed before it enters the mainline

- Tighter control over when changes get incorporated into the mainline.

A companion tool of Bazaar’s called Bundle Buggy can be very useful for tracking what changes are up for review, their status and reviewer comments.

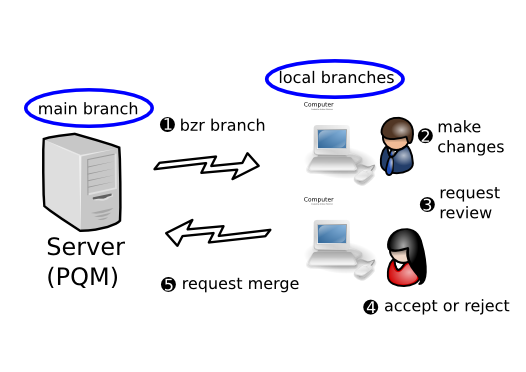

In this workflow, each developer has their own branch or branches, plus read-only access to the mainline. A software gatekeeper has commit rights to the main branch. When a developer wants their work merged, they request another person to review it. Once it has passed review, either the original author or the reviewer asks the gatekeeper software to merge it, depending on team policies. The gatekeeper software does a merge, a compile, and runs the test suite. If and only if the code passes, it is merged into the mainline.

Note: As an alternative, the review step can be skipped and the author can submit the change to the automatic gatekeeper without it. (This is particularly appropriate when using practices such as Pair Programming that effectively promote just-in-time reviews instead of reviewing code as a separate step.)

Advantages over Decentralized with human gatekeeper:

- Code is always tested before it enters the mainline (so the integrity of the mainline is higher)

- Scales better as teams grow.

A companion tool of Bazaar’s called Patch Queue Manager (PQM) can provide the automated gatekeeper capability.

For an in-depth look at how to implement each of the workflows above, see chapters 3 to 6 in this manual. First though, chapter 2 explains some important pre-requisites including installation, general usage instructions and configuration tips.

Bazaar packages are available for most popular GNU/Linux distributions including Ubuntu, Debian, Red Hat and Gentoo. See http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/Download for the latest instructions.

For Windows users, an installer is available that includes the core Bazaar package together with necessary pre-requisites and some useful plug-ins. See http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/Download for the latest instructions.

Note: If you are running Cygwin on Windows, a Bazaar for Cygwin package is available and ought to be used instead of the Windows version.

Beyond Linux and Windows, Bazaar packages are available for a large range of other operating systems include Mac OS X, FreeBSD and Solaris. See http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/Download for the latest instructions.

If you wish to install Bazaar from scratch rather than using a pre-built package, the steps are:

- If it is not installed already, install Python 2.6 or later.

- Download the bazaar-xxx.tar.gz file (where xxx is the version number) from http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/Download or from Launchpad (https://launchpad.net/~bzr/).

- Unpack the archive using tar, WinZip or equivalent.

- Put the created directory on your PATH.

To test the installation, try running the bzr command like this:

bzr version

This will display the version of Bazaar you have installed. If this doesn’t work, please contact us via email or IRC so we can help you get things working.

Instead of adding the directory to your PATH, you can install bzr into the system locations using:

python setup.py install

If you do not have a compiler, or do not have the python development tools installed, bzr supplies a (slower) pure-python implementation of all extensions. You can install without compiling extensions with:

python setup.py install build_ext --allow-python-fallback

You may wish to always be using the very latest development version of Bazaar. Note that this is not recommended for the majority of users as there is an increased risk of bugs. On the other hand, the development version is remarkably solid (thanks to the processes we follow) and running it makes it easier for you to send us changes for bugs and improvements. It also helps us by having more people testing the latest software.

Here are the steps to follow:

Install Bazaar using one of the methods given above.

Get a copy of the development version like this:

bzr branch lp:bzrPut the created directory on your PATH.

Advanced users may also wish to build the optional C extensions for greater speed. This can be done using make and requires pyrex and a C compiler. Please contact us on email or IRC if you need assistance with this.

It’s easy to have multiple versions of Bazaar installed and to switch between them. To do this, simply provide the full pathname to the bzr command you wish to run. The relevant libraries will be automatically detected and used. Of course, if you do not provide a pathname, then the bzr used will be the one found on your system path as normal.

Note that this capability is particularly useful if you wish to run (or test) both the latest released version and the development version say.

There are numerous user interfaces available for Bazaar. The core package provides a command line tool called bzr and graphical user interfaces (GUIs) are available as plug-ins.

The syntax is:

bzr [global-options] command [options and arguments]

Global options affect how Bazaar operates and can appear either before or after command. Command specific options must appear after the command but may be given either before, during or after any command-specific arguments.

Some options are legal for all commands as shown below.

Short form Long form Description -h –help get help -v –verbose be more verbose -q –quiet be more quiet

Quiet mode implies that only errors and warnings are displayed. This can be useful in scripts.

Note: Most commands typically only support one level of verbosity though that may change in the future. To ask for a higher level of verbosity, simply specify the -v option multiple times.

Bazaar comes with a built-in on-line help system, accessed through:

bzr help

You can ask for help on a command, or on non-command topics. To see a list of available help of each kind, use either:

bzr help commands

bzr help topics

For help on a particular command, use either of these forms:

bzr help status

bzr status --help

If you wish to search the help or read it as a larger document, the information is also available in the Bazaar User Reference.

One function of a version control system is to keep track of who changed what. In a decentralized system, that requires an identifier for each author that is globally unique. Most people already have one of these: an email address. Bazaar is smart enough to automatically generate an email address by looking up your username and hostname. If you don’t like the guess that Bazaar makes, then use the whoami command to set the identifier you want:

% bzr whoami "Your Name <email@example.com>"

If whoami is used without an argument, the current value is displayed.

If your network requires that you use an HTTP proxy for outbound connections, you must set the http_proxy variable. If the proxy is also required for https connections, you need to set https_proxy too. If you need these and don’t have them set, you may find that connections to Launchpad or other external servers fail or time out.

On Unix you typically want to set these in /etc/environment or ~/.bash_profile and on Windows in the user profile.

http_proxy=http://proxy.example.com:3128/

https_proxy=http://proxy.example.com:3128/

The no_proxy variable can be set to a comma-separated list of hosts which shouldn’t be reached by the proxy. (See <http://docs.python.org/library/urllib.html> for more details.)

As shown in the example above, there are various ways to configure Bazaar, they all share some common properties though. An option has:

Options are grouped in various contexts so the option name uniquely identifies it in this context. When needed, options can be made persistent by recording them in a configuration file.

Configuration files are located in $HOME/.bazaar on Unix and C:\Documents and Settings\<username>\Application Data\Bazaar\2.0 on Windows. There are three primary configuration files in this location:

Each branch can also contain a configuration file that sets values specific to that branch. This file is found at .bzr/branch/branch.conf within the branch. This file is visible to all users of a branch. If you wish to override one of the values for a branch with a setting that is specific to you, then you can do so in locations.conf.

Here is sample content of bazaar.conf after setting an email address using the whoami command:

[DEFAULT]

email = Your Name <email@example.com>

For further details on the syntax and configuration settings supported, see Configuration Settings in the Bazaar User Reference.

To look at all the currently defined options, you can use the following command:

bzr config

bzr implements some rules to decide where to get the value of a configuration option.

The current policy is to examine the existing configurations files in a given order for matching definitions.

- locations.conf is searched first for a section whose name matches the location considered (working tree, branch or remote branch),

- the current branch.conf is searched next,

- bazaar.conf is searched next,

- finally, some options can have default values generally defined in the code itself and not displayed by bzr config (see Configuration Settings).

This is better understood by using `bzr config with no arguments, which will display some output of the form:

locations:

post_commit_to = commits@example.com

news_merge_files = NEWS

branch:

parent_location = bzr+ssh://bazaar.launchpad.net/+branch/bzr/

nickname = config-modify

push_location = bzr+ssh://bazaar.launchpad.net/~vila/bzr/config-modify/

bazaar:

debug_flags = hpss,

Each configuration file is associated with a given scope whose name is displayed before each set of defined options.

If you need to look at a specific option, you can use:

bzr config <option>

This will display only the option value and is intended to be used in scripts.

To set an option to a given value use:

bzr config opt=value

An option value can reference another option by enclosing it in curly braces:

bzr config opt={other_opt}/subdir

If other_opt is set to 'root, bzr config opt will display:

root/subdir

Note that when --all is used, the references are left as-is to better reflect the content of the config files and make it easier to organize them:

bzr config --all .*opt

bazaar:

[DEFAULT]

opt = {other_opt}/subdir

other_opt = root

To remove an option use:

bzr config --remove opt

Some commands and plugins provide custom processing on files matching certain patterns. Per-user rule-based preferences are defined in BZR_HOME/rules.

For further information on how rules are searched and the detailed syntax of the relevant files, see Rules in the Bazaar User Reference.

When you give a program name or command line in configuration, you can quote to include special characters or whitespace. The same rules are used across all platforms.

The rules are: strings surrounded by double-quotes are interpreted as single “words” even if they contain whitespace, and backslash may be used to quote quotation marks. For example:

BZR_EDITOR="C:\Program Files\My Editor\myeditor.exe"

Aliases are an easy way to create shortcuts for commonly-typed commands, or to set defaults for commands.

Command aliases can be defined in the [ALIASES] section of your bazaar.conf file. Aliases start with the alias name, then an equal sign, then a command fragment. Here’s an example ALIASES section:

[ALIASES]

recentlog=log -r-3..-1

ll=log --line -r-10..-1

commit=commit --strict

diff=diff --diff-options -p

Here are the explanations of the examples above:

- The first alias makes a new recentlog command that shows the logs for the last three revisions

- The ll alias shows the last 10 log entries in line format.

- the commit alias sets the default for commit to refuse to commit if new files in the tree are not recognized.

- the diff alias adds the coveted -p option to diff

The aliases defined above would be used like so:

% bzr recentlog

% bzr ll

% bzr commit

% bzr diff

- You can override a portion of the options given in an alias by specifying the new part on the command-line. For example, if you run lastlog -r-5.., you will only get five line-based log entries instead of 10. Note that all boolean options have an implicit inverse, so you can override the commit alias with commit --no-strict.

- Aliases can override the standard behaviour of existing commands by giving an alias name that is the same as the original command. For example, default commit is changed with commit=commit --strict.

- Aliases cannot refer to other aliases. In other words making a lastlog alias and referring to it with a ll alias will not work. This includes aliases that override standard commands.

- Giving the --no-aliases option to the bzr command will tell it to ignore aliases for that run. For example, running bzr --no-aliases commit will perform a standard commit instead, not do a commit --strict.

A plugin is an external component for Bazaar that is typically made by third parties. A plugin is capable of augmenting Bazaar by adding new functionality. A plugin can also change current Bazaar behavior by replacing current functionality. Sample applications of plugins are:

The sky is the limit for the customization that can be done through plugins. In fact, plugins often work as a way for developers to test new features for Bazaar prior to inclusion in the official codebase. Plugins are helpful at feature retirement time as well, e.g. deprecated file formats may one day be removed from the Bazaar core and be made available as a plugin instead.

Plugins are good for users, good for external developers and good for Bazaar itself.

We keep our list of plugins on the http://wiki.bazaar.canonical.com/BzrPlugins page.

Installing a plugin is very easy! If not already created, create a plugins directory under your Bazaar configuration directory, ~/.bazaar/ on Unix and C:\Documents and Settings\<username>\Application Data\Bazaar\2.0\ on Windows. Within this directory (referred to as $BZR_HOME below), each plugin is placed in its own subdirectory.

Plugins work particularly well with Bazaar branches. For example, to install the bzrtools plugins for your main user account on GNU/Linux, one can perform the following:

bzr branch http://panoramicfeedback.com/opensource/bzr/bzrtools

~/.bazaar/plugins/bzrtools

When installing plugins, the directories that you install them in must be valid python identifiers. This means that they can only contain certain characters, notably they cannot contain hyphens (-). Rather than installing bzr-gtk to $BZR_HOME/plugins/bzr-gtk, install it to $BZR_HOME/plugins/gtk.

If you have the necessary permissions, plugins can also be installed on a system-wide basis. One can additionally override the personal plugins location by setting the environment variable BZR_PLUGIN_PATH (see User Reference for a detailed explanation).

To do this, use the plugins command like this:

bzr plugins

The name, location and version of each plugin installed will be displayed.

New commands added by plugins can be seen by running bzr help commands. The commands provided by a plugin are shown followed by the name of the plugin in brackets.

Here is a sample of some of the more popular plugins.

Category Name Description GUI QBzr Qt-based GUI tools GUI bzr-gtk GTK-based GUI tools GUI bzr-eclipse Eclipse integration General bzrtools misc. enhancements including shelf General difftools external diff tool helper General extmerge external merge tool helper Integration bzr-svn use Subversion as a repository Migration cvsps migrate CVS patch-sets

If you wish to write your own plugins, it is not difficult to do. See Writing a plugin in the appendices to get started.

Хотя Bazaar во многом похож на другие инструменты контроля версий, есть некоторые важные различия, которые не всегда очевидны на первый взгляд. Этот раздел пытается объяснить некоторые вещи, который пользователь должен знать чтобы разбираться в Bazaar, т.е. глубоко его понимать.

Заметьте: чтобы использовать Bazaar совсем необязательно полностью понимать этот раздел. Вы можете просмотреть этот раздел сейчас и вернуться к нему позже.

All revisions in the mainline of a branch have a simple increasing integer. (First commit gets 1, 10th commit gets 10, etc.) This makes them fairly natural to use when you want to say “grab the 10th revision from my branch”, or “fixed in revision 3050”.

For revisions which have been merged into a branch, a dotted notation is used (e.g., 3112.1.5). Dotted revision numbers have three numbers [2]. The first number indicates what mainline revision change is derived from. The second number is the branch counter. There can be many branches derived from the same revision, so they all get a unique number. The third number is the number of revisions since the branch started. For example, 3112.1.5 is the first branch from revision 3112, the fifth revision on that branch.

| [2] | Versions prior to bzr 1.2 used a slightly different algorithm. Some nested branches would get extra numbers (such as 1.1.1.1.1) rather than the simpler 3-number system. |

Imagine a project with multiple developers contributing changes where many changes consist of a series of commits. To give a concrete example, consider the case where:

- The tip of the project’s trunk is revision 100.

- Mary makes 3 changes to deliver feature X.

- Bill makes 4 changes to deliver feature Y.

If the developers are working in parallel and using a traditional centralized VCS approach, the project history will most likely be linear with Mary’s changes and Bill’s changes interleaved. It might look like this:

107: Add documentation for Y

106: Fix bug found in testing Y

105: Fix bug found in testing X

104: Add code for Y

103: Add documentation for X

102: Add code and tests for X

101: Add tests for Y

100: ...

Many teams use this approach because their tools make branching and merging difficult. As a consequence, developers update from and commit to the trunk frequently, minimizing integration pain by spreading it over every commit. If you wish, you can use Bazaar exactly like this. Bazaar does offer other ways though that you ought to consider.

An alternative approach encouraged by distributed VCS tools is to create feature branches and to integrate those when they are ready. In this case, Mary’s feature branch would look like this:

103: Fix bug found in testing X

102: Add documentation for X

101: Add code and tests for X

100: ...

And Bill’s would look like this:

104: Add documentation for Y

103: Fix bug found in testing Y

102: Add code for Y

101: Add tests for Y

100: ...

If the features were independent and you wanted to keep linear history, the changes could be pushed back into the trunk in batches. (Technically, there are several ways of doing that but that’s beyond the scope of this discussion.) The resulting history might look like this:

107: Fix bug found in testing X

106: Add documentation for X

105: Add code and tests for X

104: Add documentation for Y

103: Fix bug found in testing Y

102: Add code for Y

101: Add tests for Y

100: ...

While this takes a bit more effort to achieve, it has some advantages over having revisions randomly intermixed. Better still though, branches can be merged together forming a non-linear history. The result might look like this:

102: Merge feature X

100.2.3: Fix bug found in testing X

100.2.2: Add documentation for X

100.2.1: Add code and tests for X

101: Merge feature Y

100.1.4: Add documentation for Y

100.1.3: Fix bug found in testing Y

100.1.2: Add code for Y

100.1.1: Add tests for Y

100: ...

Or more likely this:

102: Merge feature X

100.2.3: Fix bug

100.2.2: Add documentation

100.2.1: Add code and tests

101: Merge feature Y

100.1.4: Add documentation

100.1.3: Fix bug found in testing

100.1.2: Add code

100.1.1: Add tests

100: ...

This is considered good for many reasons:

- It makes it easier to understand the history of a project. Related changes are clustered together and clearly partitioned.

- You can easily collapse history to see just the commits on the mainline of a branch. When viewing the trunk history like this, you only see high level commits (instead of a large number of commits uninteresting at this level).

- If required, it makes backing out a feature much easier.

- Continuous integration tools can be used to ensure that all tests still pass before committing a merge to the mainline. (In many cases, it isn’t appropriate to trigger CI tools after every single commit as some tests will fail during development. In fact, adding the tests first - TDD style - will guarantee it!)

In summary, the important points are:

Organize your work using branches.

Integrate changes using merge.

Ordered revision numbers and hierarchy make history easier to follow.

As explained above, Bazaar makes the distinction between:

- mainline revisions, i.e. ones you committed in your branch, and

- merged revisions, i.e. ones added as ancestors by committing a merge.

Each branch effectively has its own view of history, i.e. different branches can give the same revision a different “local” revision number. Mainline revisions always get allocated single number revision numbers while merged revisions always get allocated dotted revision numbers.

To extend the example above, here’s what the revision history of Mary’s branch would look like had she decided to merge the project trunk into her branch after completing her changes:

104: Merge mainline

100.2.1: Merge feature Y

100.1.4: Add documentation

100.1.3: Fix bug found in testing

100.1.2: Add code

100.1.1: Add tests

103: Fix bug found in testing X

102: Add documentation for X

101: Add code and tests for X

100: ...

Once again, it’s easy for Mary to look at just her top level of history to see the steps she has taken to develop this change. In this context, merging the trunk (and resolving any conflicts caused by doing that) is just one step as far as the history of this branch is concerned.

It’s important to remember that Bazaar is not changing history here, nor is it changing the global revision identifiers. You can always use the latter if you really want to. In fact, you can use the branch specific revision numbers when communicating as long as you provide the branch URL as context. (In many Bazaar projects, developers imply the central trunk branch if they exchange a revision number without a branch URL.)

Merges do not change revision numbers in a branch, though they do allocate local revision numbers to newly merged revisions. The only time Bazaar will change revision numbers in a branch is when you explicitly ask it to mirror another branch.

Note: Revisions are numbered in a stable way: if two branches have the same revision in their mainline, all revisions in the ancestry of that revision will have the same revision numbers. For example, if Alice and Bob’s branches agree on revision 10, they will agree on all revisions before that.

Обычно, если вы следовали ранее полученным советам - организовать вашу работу в ветках и использовать объединение для сотрудничества - вы обнаружите что чаще всего Bazaar делает то что вы ожидаете.

В следующих главах, мы проверим различный способы использования Bazaar, начиная с самого простого: использование Bazaar для личных проектов.

Some tools are designed to make individuals productive (e.g. editors) while other tools (e.g. back-end services) are focused on making teams or whole companies more productive. Version control tools have traditionally been in the latter camp.

One of the cool things about Bazaar is that it is so easy to setup that version control can now be treated as a personal productivity tool. If you wish to record changes to files for the purposes of checkpointing good known states or tracking history, it is now easy to do so. This chapter explains how.

If you are creating your own masterpiece, whether that be a software project or a set of related documents, the typical workflow looks like this:

Even if you will always be working as part of a team, the tasks covered in this chapter will be the basis of what you’ll be doing so it’s a good place to start.

If you already have a tree of source code (or directory of documents) you wish to put under version control, here are the commands to use:

cd my-stuff

bzr init

bzr add

bzr commit -m "Initial import"

bzr init creates a .bzr directory in the top level directory (my-stuff in the example above). Note that:

- Bazaar has everything it needs in that directory - you do not need to setup a database, web server or special service to use it

- Bazaar is polite enough to only create one .bzr in the directory given, not one in every subdirectory thereof.

bzr add then finds all the files and directories it thinks ought to be version controlled and registers them internally. bzr commit then records a snapshot of the content of these and records that information, together with a commit message.

More information on init, add and commit will be provided later. For now, the important thing to remember is the recipe above.

If you are starting a project from scratch, you can also use the recipe above, after creating an empty directory first of course. For efficiency reasons that will be explored more in later chapters though, it is a good idea to create a repository for the project at the top level and to nest a main branch within it like this:

bzr init-repo my.repo

cd my.repo

bzr init my.main

cd my.main

hack, hack, hack

bzr add

bzr commit -m "Initial import"

Some users prefer a name like trunk or dev to main. Choose whichever name makes the most sense to you.

Note that the init-repo and init commands both take a path as an argument and will create that path if it doesn’t already exist.

As explained earlier, bzr add finds and registers all the things in and under the current directory that Bazaar thinks ought to be version controlled. These things may be:

- files

- directories

- symbolic links.

Bazaar has default rules for deciding which files are interesting and which ones are not. You can tune those rules as explained in Ignoring files below.

Unlike many other VCS tools, Bazaar tracks directories as first class items. As a consequence, empty directories are correctly supported - you don’t need to create a dummy file inside a directory just to ensure it gets tracked and included in project exports.

For symbolic links, the value of the symbolic link is tracked, not the content of the thing the symbolic link is pointing to.

Note: Support for tracking projects-within-projects (“nested trees”) is currently under development. Please contact the Bazaar developers if you are interested in helping develop or test this functionality.

In some cases, you may want or need to explicitly nominate the things to register rather than leave it up to Bazaar to find things. To do this, simply provide paths as arguments to the add command like this:

bzr add fileX dirY/

Adding a directory implicitly adds all interesting things underneath it.

Many source trees contain some files that do not need to be versioned, such as editor backups, object or bytecode files, and built programs. You can simply not add them, but then they’ll always crop up as unknown files. You can also tell Bazaar to ignore these files by adding them to a file called .bzrignore at the top of the tree.

This file contains a list of file wildcards (or “globs”), one per line. Typical contents are like this:

*.o

*~

*.tmp

*.py[co]

If a glob contains a slash, it is matched against the whole path from the top of the tree; otherwise it is matched against only the filename. So the previous example ignores files with extension .o in all subdirectories, but this example ignores only config.h at the top level and HTML files in doc/:

./config.h

doc/*.html

To get a list of which files are ignored and what pattern they matched, use bzr ignored:

% bzr ignored

config.h ./config.h

configure.in~ *~

Note that ignore patterns are only matched against non-versioned files, and control whether they are treated as “unknown” or “ignored”. If a file is explicitly added, it remains versioned regardless of whether it matches an ignore pattern.

The .bzrignore file should normally be versioned, so that new copies of the branch see the same patterns:

% bzr add .bzrignore

% bzr commit -m "Add ignore patterns"

The command bzr ignore PATTERN can be used to easily add PATTERN to the .bzrignore file (creating it if necessary and registering it to be tracked by Bazaar). Removing and modifying patterns are done by directly editing the .bzrignore file.

There are some ignored files which are not project specific, but more user specific. Things like editor temporary files, or personal temporary files. Rather than add these ignores to every project, bzr supports a global ignore file in ~/.bazaar/ignore [3]. It has the same syntax as the per-project ignore file.

| [3] | On Windows, the users configuration files can be found in the application data directory. So instead of ~/.bazaar/branch.conf the configuration file can be found as: C:\Documents and Settings\<username>\Application Data\Bazaar\2.0\branch.conf. The same is true for locations.conf, ignore, and the plugins directory. |

Once you have completed some work, it’s a good idea to review your changes prior to permanently recording it. This way, you can make sure you’ll be committing what you intend to.

Two bzr commands are particularly useful here: status and diff.

The status command tells you what changes have been made to the working directory since the last revision:

% bzr status

modified:

foo

bzr status hides “boring” files that are either unchanged or ignored. The status command can optionally be given the name of some files or directories to check.

The diff command shows the full text of changes to all files as a standard unified diff. This can be piped through many programs such as ‘’patch’‘, ‘’diffstat’‘, ‘’filterdiff’’ and ‘’colordiff’‘:

% bzr diff

=== added file 'hello.txt'

--- hello.txt 1970-01-01 00:00:00 +0000

+++ hello.txt 2005-10-18 14:23:29 +0000

@@ -0,0 +1,1 @@

+hello world

With the -r option, the tree is compared to an earlier revision, or the differences between two versions are shown:

% bzr diff -r 1000.. # everything since r1000

% bzr diff -r 1000..1100 # changes from 1000 to 1100

To see the changes introduced by a single revision, you can use the -c option to diff.

% bzr diff -c 1000 # changes from r1000

# identical to -r999..1000

The --diff-options option causes bzr to run the external diff program, passing options. For example:

% bzr diff --diff-options --side-by-side foo

Some projects prefer patches to show a prefix at the start of the path for old and new files. The --prefix option can be used to provide such a prefix. As a shortcut, bzr diff -p1 produces a form that works with the command patch -p1.

When the working tree state is satisfactory, it can be committed to the branch, creating a new revision holding a snapshot of that state.

The commit command takes a message describing the changes in the revision. It also records your userid, the current time and timezone, and the inventory and contents of the tree. The commit message is specified by the -m or --message option. You can enter a multi-line commit message; in most shells you can enter this just by leaving the quotes open at the end of the line.

% bzr commit -m "added my first file"

You can also use the -F option to take the message from a file. Some people like to make notes for a commit message while they work, then review the diff to make sure they did what they said they did. (This file can also be useful when you pick up your work after a break.)

If you use neither the -m nor the -F option then bzr will open an editor for you to enter a message. The editor to run is controlled by your $VISUAL or $EDITOR environment variable, which can be overridden by the editor setting in ~/.bazaar/bazaar.conf; $BZR_EDITOR will override either of the above mentioned editor options. If you quit the editor without making any changes, the commit will be cancelled.

The file that is opened in the editor contains a horizontal line. The part of the file below this line is included for information only, and will not form part of the commit message. Below the separator is shown the list of files that are changed in the commit. You should write your message above the line, and then save the file and exit.

If you would like to see the diff that will be committed as you edit the message you can use the --show-diff option to commit. This will include the diff in the editor when it is opened, below the separator and the information about the files that will be committed. This means that you can read it as you write the message, but the diff itself wont be seen in the commit message when you have finished. If you would like parts to be included in the message you can copy and paste them above the separator.

If you give file or directory names on the commit command line then only the changes to those files will be committed. For example:

% bzr commit -m "documentation fix" commit.py

By default bzr always commits all changes to the tree, even if run from a subdirectory. To commit from only the current directory down, use:

% bzr commit .

If you didn’t actually write the changes that you are about to commit, for instance if you are applying a patch from someone else, you can use the --author commit option to give them credit for the change:

% bzr commit --author "Jane Rey <jrey@example.com>"

The person that you specify there will be recorded as the “author” of the revision, and you will be recorded as the “committer” of the revision.

If more than one person works on the changes for a revision, for instance if you are pair-programming, then you can record this by specifying --author multiple times:

% bzr commit --author "Jane Rey <jrey@example.com>" \

--author "John Doe <jdoe@example.com>"

The bzr log command shows a list of previous revisions.

As with bzr diff, bzr log supports the -r argument:

% bzr log -r 1000.. # Revision 1000 and everything after it

% bzr log -r ..1000 # Everything up to and including r1000

% bzr log -r 1000..1100 # changes from 1000 to 1100

% bzr log -r 1000 # The changes in only revision 1000

As distributed VCS tools like Bazaar make merging much easier than it is in central VCS tools, the history of a branch may often contain lines of development splitting off the mainline and merging back in at a later time. Technically, the relationship between the numerous revision nodes is known as a Directed Acyclic Graph or DAG for short.

In many cases, you typically want to see the mainline first and drill down from there. The default behaviour of log is therefore to show the mainline and indicate which revisions have nested merged revisions. To explore the merged revisions for revision X, use the following command:

bzr log -n0 -rX

To see all revisions and all their merged revisions:

bzr log -n0

Note that the -n option is used to indicate the number of levels to display where 0 means all. If that is too noisy, you can easily adjust the number to only view down so far. For example, if your project is structured with a top level gatekeeper merging changes from team gatekeepers, bzr log shows what the top level gatekeeper did while bzr log -n2 shows what the team gatekeepers did. In the vast majority of cases though, -n0 is fine.

The log command has several options that are useful for tuning the output. These include:

- --forward presents the log in chronological order, i.e. the most recent revisions are displayed last.

- the --limit option controls the maximum number of revisions displayed.

See the online help for the log command or the User Reference for more information on tuning the output.

It is often useful to filter the history so that it only applies to a given file. To do this, provide the filename to the log command like this:

bzr log foo.py

To get the contents of a file at a given version, use the cat command like this:

bzr cat -r X file

where X is the revision identifier and file is the filename. This will send output to the standard output stream so you’ll typically want to pipe the output through a viewing tool (like less or more) or redirect it like this:

bzr cat -r -2 foo.py | less

bzr cat -r 1 foo.py > /tmp/foo-1st-version.py

History browsing is one area where GUI tools really make life easier. Bazaar has numerous plug-ins that provide this capability including QBzr and bzr-gtk. See Using plugins for details on how to install these if they are not already installed.

To use the graphical viewer from QBzr:

bzr qlog

To use the graphical viewer from bzr-gtk:

bzr viz

viz is actually a built-in alias for visualize so use the longer command name if you prefer.

The export command is used to package a release, i.e. to take a copy of the files and directories in a branch and package them into a fresh directory or archive. For example, this command will package the last committed version into a tar.gz archive file:

bzr export ../releases/my-stuff-1.5.tar.gz

The export command uses the suffix of the archive file to work out the type of archive to create as shown below.

Supported formats Autodetected by extension dir (none) tar .tar tbz2 .tar.bz2, .tbz2 tgz .tar.gz, .tgz zip .zip

If you wish to package a revision other than the last one, use the -r option. If you wish to tune the root directory inside the archive, use the --root option. See the online help or User Reference for further details on the options supported by export.

Rather than remembering which version was used to package a release, it’s useful to define a symbolic name for a version using the tag command like this:

bzr tag version-1-5

That tag can be used later whenever a revision identifier is required, e.g.:

bzr diff -r tag:version-1-5

To see the list of tags defined in a branch, use the tags command.

Bazaar has been designed to make it easy to recover from mistakes as explained below.

If you accidentally put the wrong tree under version control, simply delete the .bzr directory.

If you accidentally register a file using add that you don’t want version controlled, you can use the remove command to tell Bazaar to forget about it.

remove has been designed to Do the Safe Thing in that it will not delete a modified file. For example:

bzr add foo.html

(oops - didn't mean that)

bzr remove foo.html

This will complain about the file being modified or unknown. If you want to keep the file, use the --keep option. Alternatively, if you want to delete the file, use the --force option. For example:

bzr add foo.html

(oops - didn't mean that)

bzr remove --keep foo.html

(foo.html left on disk, but deregistered)

On the other hand, the unchanged TODO file is deregistered and removed from disk without complaint in this example:

bzr add TODO

bzr commit -m "added TODO"

(hack, hack, hack - but don't change TODO)

bzr remove TODO

(TODO file deleted)

Note: If you delete a file using your file manager, IDE or via an operating system command, the commit command will implicitly treat it as removed.

One of the reasons for using a version control tool is that it lets you easily checkpoint good tree states while working. If you decide that the changes you have made since the last commit ought to be thrown away, the command to use is revert like this:

bzr revert

As a precaution, it is good practice to use bzr status and bzr diff first to check that everything being thrown away really ought to be.

If you want to undo changes to a particular file since the last commit but keep all the other changes in the tree, pass the filename as an argument to revert like this:

bzr revert foo.py

If you make a commit and really didn’t mean to, use the uncommit command to undo it like this:

bzr uncommit

Unlike revert, uncommit leaves the content of your working tree exactly as it is. That’s really handy if you make a commit and accidently provide the wrong error message. For example:

bzr commit -m "Fix bug #11"

(damn - wrong bug number)

bzr uncommit

bzr commit -m "Fix bug #1"

Another common reason for undoing a commit is because you forgot to add one or more files. Some users like to alias commit to commit --strict so that commits fail if unknown files are found in the tree.

Tags for uncommitted revisions are removed from the branch unless --keep-tags was specified.

Note: While the merge command is not introduced until the next chapter, it is worth noting now that uncommit restores any pending merges. (Running bzr status after uncommit will show these.) merge can also be used to effectively undo just a selected commit earlier in history. For more information on merge, see Merging changes in the next chapter and the Bazaar User Reference.

You can use the -r option to undo several commits like this:

bzr uncommit -r -3

If your reason for doing this is that you really want to back out several changes, then be sure to remember that uncommit does not change your working tree: you’ll probably need to run the revert command as well to complete the task. In many cases though, it’s arguably better to leave your history alone and add a new revision reflecting the content of the last good state.

If you make an unwanted change but it doesn’t make sense to uncommit it (because that code has been released to users say), you can use revert to take your working tree back to the desired state. For example:

% bzr commit "Fix bug #5"

Committed revision 20.

(release the code)

(hmm - bad fix)

bzr revert -r 19

bzr commit -m "Backout fix for bug #5"

This will change your entire tree back to the state as of revision 19, which is probably only what you want if you haven’t made any new commits since then. If you have, the revert would wipe them out as well. In that case, you probably want to use Reverse cherrypicking instead to back out the bad fix.

Note: As an alternative to using an absolute revision number (like 19), you can specify one relative to the tip (-1) using a negative number like this:

bzr revert -r -2

If you have defined a tag prematurely, use the --force option of the tag command to redefine it. For example:

bzr tag 2.0-beta-1

(oops, we're not yet ready for that)

(make more commits to include more fixes)

bzr tag 2.0-beta-1 --force

If you have defined a tag and no longer want it defined, use the --delete option of the tag command to remove it. For example:

bzr tag 2.0-beta-4

(oops, we're not releasing a 4th beta)

bzr tag 2.0-beta-4 --delete

In many cases, two minds can be better than one. You may be the one who started a project and someone wishes to help, or perhaps it’s you who wants to help another. Perhaps you are both members of a larger team that have been assigned a task together as pair programmers. Either way, two people need to agree on a process, a set of guidelines and a toolset in order to work together effectively.

Imagine if you were not allowed to call someone on the phone directly and the only way to talk to them was by registering a conference call first? Companies and communities that only share code via a central VCS repository are living with a similar straitjacket to that every day. There are times when central control makes a lot of sense and times when peer-to-peer rocks. Either way, Bazaar is designed to help.

While it’s certainly not the only way to do it, the partner workflow below is a good starting point for a pair of people who wish to collaborate using Bazaar.

Over and above the tasks covered in the previous chapter, this chapter introduces two essential collaboration activities:

- getting a copy of a branch

- merging changes between branches.

Even when it’s just you working on a code base, it can be very useful to keep multiple branches around (for different releases say) and to merge changes between them as appropriate. Your “partner” may indeed be yourself.

Before someone else can get a copy of your work, you need to agree on a transfer technology. You may decide to make the top level directory of your branch a network share, an approach familiar to Windows users. Linux and OS X users might prefer access to be via SFTP, a secure protocol built-in to most SSH servers. Bazaar is very flexible in this regard with support for lots of protocols some of which are given below.

As indicated above, branches are identified using URLs with the prefix indicating the transfer technology. If no prefix is given, normal filenames are assumed. For a complete list of supported protocols, see the urlspec online help topic or the URL Identifiers section of the Bazaar User Reference.

To get a branch based on an existing branch, use the branch command. The syntax is:

bzr branch URL [directory]

If a directory is not given, one is created based on the last part of the URL. Here are some examples showing a drive qualified path (M:/) and an SFTP URL respectively:

bzr branch M:/cool-trunk

bzr branch sftp://bill@mary-laptop/cool-repo/cool-trunk

This example shows explicitly giving the directory name to use for the new branch:

bzr branch /home/mary/cool-repo/cool-trunk cool

Depending on the size of the branch being transferred and the speed and latency of the network between your computer and the source branch, this initial transfer might take some time. Subsequent updates should be much faster as only the changes are transferred then.

Keep in mind that Bazaar is transferring the complete history of the branch, not just the latest snapshot. As a consequence, you can be off the network (or disconnected from the network share) after branch completes but you’ll still be able to log and diff the history of the branch as much as you want. Furthermore, these operations are quick as the history is stored locally.

Note that Bazaar uses smart compression technology to minimize the amount of disk space required to store version history. In many cases, the complete history of a project will take up less disk space than the working copy of the latest version.

As explained in later chapters, Bazaar also has support for lightweight checkouts of a branch, i.e. working trees with no local storage of history. Of course, disconnected usage is not available then but that’s a tradeoff you can decide to make if local disk space is really tight for you. Support for limited lookback into history - history horizons - is currently under development as well.

If you wish to see information about a branch including where it came from, use the info command. For example:

bzr info cool

If no branch is given, information on the current branch is displayed.

Once someone has their own branch of a project, they can make and commit changes in parallel to any development proceeding on the original branch. Pretty soon though, these independent lines of development will need to be combined again. This process is known as merging.

To incorporate changes from another branch, use the merge command. Its syntax is:

bzr merge [URL]

If no URL is given, a default is used, initially the branch this branch originated from. For example, if Bill made a branch from Mary’s work, he can merge her subsequent changes by simply typing this:

bzr merge

On the other hand, Mary might want to merge into her branch the work Bill has done in his. In this case, she needs to explicitly give the URL the first time, e.g.:

bzr merge bzr+ssh://mary@bill-laptop/cool-repo/cool-trunk

This sets the default merge branch if one is not already set. Use --no-remember to avoid setting it. To change the default after it is set, use the --remember option.

A variety of algorithms exist for merging changes. Bazaar’s default algorithm is a variation of 3-way merging which works as follows. Given an ancestor A and two branches B and C, the following table provides the rules used.

A B C Result Comment x x x x unchanged x x y y line from C x y x y line from B x y z ? conflict

Note that some merges can only be completed with the assistance of a human. Details on how to resolve these are given in Resolving conflicts.

After any conflicts are resolved, the merge needs to be committed. For example:

bzr commit -m "Merged Mary's changes"

Even if there are no conflicts, an explicit commit is still required. Unlike some other tools, this is considered a feature in Bazaar. A clean merge is not necessarily a good merge so making the commit a separate explicit step allows you to run your test suite first to verify all is good. If problems are found, you should correct them before committing the merge or throw the merge away using revert.

One of the most important features of Bazaar is distributed, high quality merge tracking. In other words, Bazaar remembers what has been merged already and uses that information to intelligently choose the best ancestor for a merge, minimizing the number and size of conflicts.

If you are a refugee from many other VCS tools, it can be really hard to “unlearn” the please-let-me-avoid-merging-at-any-cost habit. Bazaar lets you safely merge as often as you like with other people. By working in a peer-to-peer manner when it makes sense to do so, you also avoid using a central branch as an “integration swamp”, keeping its quality higher. When the change you’re collaborating on is truly ready for wider sharing, that’s the time to merge and commit it to a central branch, not before.

Merging that Just Works truly can change how developers work together.

Unlike some other tools that force you to resolve each conflict during the merge process, Bazaar merges as much as it can and then reports the conflicts. This can make conflict resolution easier because the contents of the whole post-merge tree are available to help you decide how things ought to be resolved. You may also wish to selectively run tests as you go to confirm each resolution or group or resolutions is good.

As well as being reported by the merge command, the list of outstanding conflicts may be displayed at any time by using the conflicts command. It is also included as part of the output from the status command.

When a conflict is encountered, the merge command puts embedded markers in each file showing the areas it couldn’t resolve. It also creates 3 files for each file with a conflict:

- foo.BASE

- foo.THIS

- foo.OTHER

where foo is the name of the conflicted file. In many cases, you can resolve conflicts by simply manually editing each file in question, fixing the relevant areas and removing the conflict markers as you go.

After fixing all the files in conflict, and removing the markers, ask Bazaar to mark them as resolved using the resolve command like this:

bzr resolve

Alternatively, after fixing each file, you can mark it as resolved like this:

bzr resolve foo

Among other things, the resolve command cleans up the BASE, THIS and OTHER files from your working tree.

In some cases, you may wish to try a different merge algorithm on a given file. To do this, use the remerge command nominating the file like this:

bzr remerge --weave foo

where foo is the file and weave is one of the available merge algorithms. This algorithm is particularly useful when a so-called criss-cross merge is detected, e.g. when two branches merge the same thing then merge each other. See the online help for criss-cross and remerge for further details.

If you have a GUI tool you like using to resolve conflicts, be sure to install the extmerge plugin. Once installed, it can be used like this:

bzr extmerge foo

where foo is the conflicted file. Rather than provide a list of files to resolve, you can give the --all option to implicitly specify all conflicted files.

The extmerge command uses the tool specified by the external_merge setting in your bazaar.conf file. If not set, it will look for some popular merge tools such as kdiff3 or opendiff, the latter being a command line interface to the FileMerge utility in OS X.

When two or more people are working on files, it can be highly useful at times to see who created or last changed certain content. To do this, using the annotate command like this:

bzr annotate readme.txt

If you are a pessimist or an optimist, you might prefer to use one of built-in aliases for annotate: blame or praise. Either way, this displays each line of the file together with information such as:

- who changed it last

- when it was last changed

- the commit message.

The various GUI plugins for Bazaar provide graphical tools for viewing annotation information. For example, the bzr-gtk plugin provides a GUI tool for this that can be launched using the gannotate command:

bzr gannotate readme.txt

The GUI tools typically provide a much richer display of interesting information (e.g. all the changes in each commit) so you may prefer them over the text-based command.

Rather than working in parallel and occasionally merging, it can be useful at times to work in lockstep, i.e. for multiple people to be continuously committing changes to a central location, merging their work with the latest content before every commit.

This workflow is very familiar to users of central VCS tools like Subversion and CVS. It is also applicable to a single developer who works on multiple machines, e.g. someone who normally works on a desktop computer but travels with a laptop, or someone who uses their (Internet connected) home computer to complete office work out of hours.

If centralized development works well for your team already, that’s great. Many teams begin using Bazaar this way and experiment with alternative workflows later.

The diagram below provides an overview of the centralized workflow.

Even if your team is planning to use a more distributed workflow, many of the tasks covered in this chapter may be useful to you, particularly how to publish branches.

While the centralized workflow can be used by socially nominating any branch on any computer as the central one, in practice most teams have a dedicated server for hosting central branches.

Just as it’s best practice to use a shared repository locally, it’s advisable to put central branches in a shared repository. Note that central shared branches typically only want to store history, not working copies of files, so their enclosing repository is usually creating using the no-trees option, e.g.:

bzr init-repo --no-trees bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT

You can think of this step as similar to setting up a new cvsroot or Subversion repository. However, Bazaar gives you more flexibility in how branches may be organised in your repository. See Advanced shared repository layouts in the appendices for guidelines and examples.

There are two ways of populating a central branch with some initial content:

- Making a local branch and pushing it to a central location

- Making an empty central branch then committing content to it.

Here is an example of the first way:

bzr init-repo PROJECT (prepare local repository)

bzr init PROJECT/trunk

cd PROJECT/trunk

(copy development files)

cp -ar ~/PROJECT . (copy files in using OS-specific tools)

bzr add (populate repository; start version control)

bzr commit -m "Initial import"

(publish to central repository)

bzr push bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

Here is an example of the second way:

bzr init-repo PROJECT (prepare local repository)

cd PROJECT

bzr init bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

bzr checkout bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

cd trunk

cp -ar ~/PROJECT . (copy files in using OS-specific tools)

bzr add (populate repository; start version control)

bzr commit -m "Initial import"

(publish to central repository)

Note that committing inside a working tree created using the checkout command implicitly commits the content to the central location as well as locally. Had we used the branch command instead of checkout above, the content would have only been committed locally.

Working trees that are tightly bound to a central location like this are called checkouts. The rest of this chapter explains their numerous features in more detail.

If you have a local branch and wish to make it a checkout, use the bind command like this:

bzr bind sftp://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

This is necessary, for example, after creating a central branch using push as illustrated in the previous section.

After this, commits will be applied to the bound branch before being applied locally.

If you have a checkout and wish to make it a normal branch, use the unbind command like this:

bzr unbind

After this, commits will only be applied locally.

When working in a team using a central branch, one person needs to provide some initial content as shown in the previous section. After that, each person should use the checkout command to create their local checkout, i.e. the sandbox in which they will make their changes.

Unlike Subversion and CVS, in Bazaar the checkout command creates a local full copy of history in addition to creating a working tree holding the latest content. This means that operations such as diff and log are fast and can still be used when disconnected from the central location.

While Bazaar does its best to efficiently store version history, there are occasions when the history is simply not wanted. For example, if your team is managing the content of a web site using Bazaar with a central repository, then your release process might be as simple as updating a checkout of the content on the public web server. In this case, you probably don’t want the history downloaded to that location as doing so:

- wastes disk space holding history that isn’t needed there

- exposes a Bazaar branch that you may want kept private.

To get a history-less checkout in Bazaar, use the --lightweight option like this:

bzr checkout --lightweight sftp://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

Of course, many of the benefits of a normal checkout are lost by doing this but that’s a tradeoff you can make if and when it makes sense.

The --lightweight option only applies to checkouts, not to all branches.

Note: If your code base is really large and disk space on your computer is limited, lightweight checkouts may be the right choice for you. Be sure to consider all your options though including shared repositories, stacked branches, and reusing a checkout.

One of the important aspects of working in lockstep with others is keeping your checkout up to date with the latest changes made to the central branch. Just as you would in Subversion or CVS, you do this in Bazaar by using the update command like this:

bzr update

This gets any new revisions available in the bound branch and merges your local changes, if any.

Note that your checkout must be up to date with the bound branch before running commit. Bazaar is actually stricter about this than Subversion or CVS - you need to be up to date with the full tree, not just for the files you’ve changed. Bazaar will ask you to run update if it detects that a revision has been added to the central location since you last updated.

If the network connection to the bound branch is lost, the commit will fail. Some alternative ways of working around that are outlined next.

If you lose your network connection because you are travelling, the central server goes down, or you simply want to snapshot changes locally without publishing them centrally just yet, this workflow is for you.

If you’re working in a checkout and need/wish to commit locally only, add the --local option to the commit command like this:

bzr commit --local

If you will be or want to be disconnected from the bound branch for a while, then remembering to add --local to every commit command can be annoying. An alternative is to use the unbind command to make the checkout temporarily into a normal branch followed by the bind command at some later point in time when you want to keep in lockstep again.

Note that the bind command remembers where you were bound to last time this branch was a checkout so it isn’t necessary to enter the URL of the remote branch when you use bind after an earlier unbind.

When you make commits locally independent of ongoing development on a central branch, then Bazaar treats these as two lines of development next time you update. In this case, update does the following:

- it brings the latest revisions from the bound branch down and makes that the mainline of development within your checkout

- it moves your local changes since you last updated into a logical parallel branch

- it merges these together so that your local changes are reported as a pending merge by status.

As always, you will need to run commit after this to send your work to the central branch.

At times, it can be useful to have a single checkout as your sandbox for working on multiple branches. Some possible reasons for this include:

- saving disk space when the working tree is large

- developing in a fixed location.

In many cases, working tree disk usage swamps the size of the .bzr directory. If you want to work on multiple branches but can’t afford the overhead of a full working tree for each, reusing a checkout across multiples branches is the way to go.

On other occasions, the location of your sandbox might be configured into numerous development and testing tools. Once again, reusing a checkout across multiple branches can help.

To change where a checkout is bound to, follow these steps:

- Make sure that any local changes have been committed centrally so that no work is lost.

- Use the bind command giving the URL of the new remote branch you wish to work on.

- Make your checkout a copy of the desired branch by using the update command followed by the revert command.

Note that simply binding to a new branch and running update merges in your local changes, both committed and uncommitted. You need to decide whether to keep them or not by running either revert or commit.

An alternative to the bind+update recipe is using the switch command. This is basically the same as removing the existing branch and running checkout again on the new location, except that any uncommitted changes in your tree are merged in.

Note: As switch can potentially throw away committed changes in order to make a checkout an accurate cache of a different bound branch, it will fail by design if there are changes which have been committed locally but are not yet committed to the most recently bound branch. To truly abandon these changes, use the --force option.

With a lightweight checkout, there are no local commits and switch effectively changes which branch the working tree is associated with. One possible setup is to use a lightweight checkout in combination with a local tree-less repository. This lets you switch what you are working on with ease. For example:

bzr init-repo --no-trees PROJECT

cd PROJECT

bzr branch bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/trunk

bzr checkout --lightweight trunk my-sandbox

cd my-sandbox

(hack away)

Note that trunk in this example will have a .bzr directory within it but there will be no working tree there as the branch was created in a tree-less repository. You can grab or create as many branches as you need there and switch between them as required. For example:

(assuming in my-sandbox)

bzr branch bzr+ssh://centralhost/srv/bzr/PROJECT/PROJECT-1.0 ../PROJECT-1.0

bzr switch ../PROJECT-1.0

(fix bug in 1.0)

bzr commit -m "blah, blah blah"

bzr switch ../trunk

(go back to working on the trunk)

Note: The branches may be local only or they may be bound to remote ones (by creating them with checkout or by using bind after creating them with branch).

Distributed VCS tools offer new ways of working together, ways that better reflect the modern world we live in and ways that enable higher quality outcomes.